[This semester, the capstone of my Mystical Journeys course was a reading of Paradiso, Cantos 21-33. Over the next few weeks, I hope to develop that reading here, beginning with Canto 28. I begin here with a few introductory principles and taste of what is to come.]

#1: The Divine Comedy is not a work of eschatology; it is not about the afterlife. It is essentially about this life, here and now. This is essential to understanding Paradiso in particular.

Few ideas are more mistaken than the notion that Dante is giving us a tour of the afterlife. This is not 90 Minutes in Heaven. Dante is at no point engaged in mere speculative description. Modern eschatology emerges, if I may venture a further thesis, after the collapse of two genres: the apocalypse and the spiritual itinerary. The former is not Dante’s project.

What Dante presents us with are images, which are meant to illuminate our life here and now. They make transparent the drama of disordered love and its reordering. The pedagogical purpose of the pilgrimage, ordered to Dante’s implied return to mortal flesh, makes this clear.

#2: Dante masters, rather than being mastered by, his images, whether eschatological or cosmological. As such, he in no way represents an outmoded medieval vision of the world.

Almost as tiring as the use of the adjective “Dantean” to describe the sadistic infernalism of Middle Ages (both real and imagined) is the dismissal or ridicule of his cosmology as erroneous or outdated.

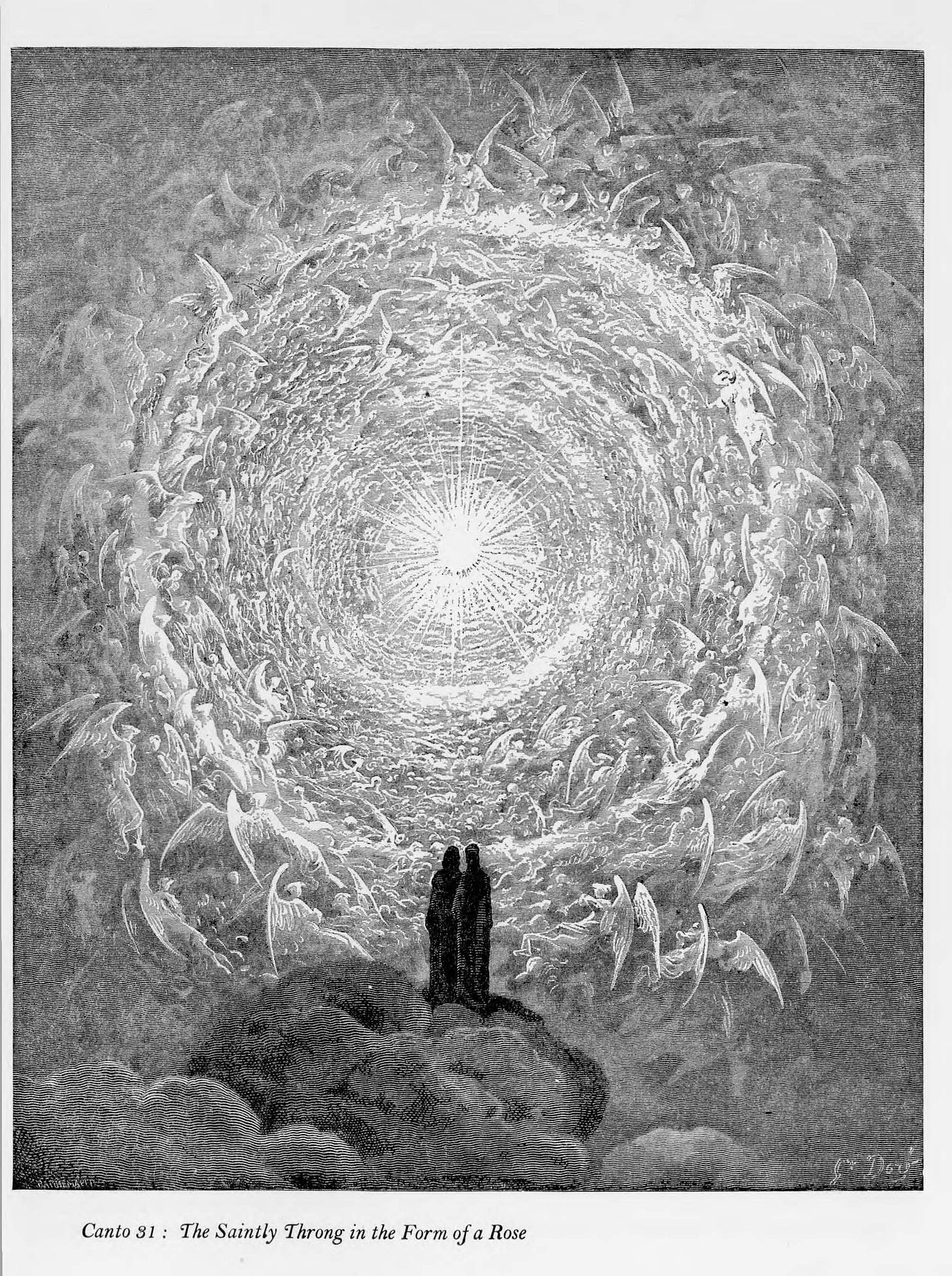

In both cases, we feel to see that these are images and Dante is free in his use of them. He will change the cosmology and “eschatology” as the necessities of thought and poetic art dictate. Notably, he departs from Thomism (more on this later) in his dynamic portrayal of Purgatory as a place of moral change. Similarly, in the course of the Paradiso Dante himself takes us to the point of destroying and even inverting the cosmology, as in the glimpse of the “spiritual solar system” (Canto 28). This freedom is typical of the spiritual itinerary, or as Henry Corbin puts it, the “visionary recital.” It is typical that in the latter stages, the pilgrim herself performs the transcendence of the images.

#3: The Divine Comedy belongs to the genre of the spiritual itinerary, which unfurls according an inexorable logic, the logic of the progress of Soul. To understand the work’s transitions is to understand the work.

One spiritual state leads to the next, if not in every case, at least in its ideal unfolding. Each part of the Comedy is organized around a particular series: in the Inferno, the vices of the Nicomachean Ethics; in the Purgatorio, the Seven Deadly Sins; and in the Paradiso (more loosely), the theological virtues. But this is not simply received terminology. Dante attempts to show how each necessarily leads to the next. If we understand the work, we should be able to see why a certain vice is the logical outworking of the previous, or why a certain heavenly sphere is the resolution of the tensions and the contradictions of the previous.

#4: In a spiritual itinerary, the Goal establishes and regulates the Way’s possibility and its logic. As such, assuming the work is not a failure, Paradiso will be in terms of form and content the work’s climax and greatest achievement.

It is frequently stated that the Paradiso is the least successful and interesting part of the Comedy, and that the most absorbing images are those of the various punishments in Hell and Purgatory.

This is perhaps a commentary on the psychology of the modern reader, but it certainly does not reflect Dante’s intention. In a spiritual itinerary, the logic of Soul’s progress is prescribed by the end sought and only understandable through that end.

It is only from the perspective of the completed journey that we understand why it was possible and why it had to unfold the way it did. If we do not see the Paradiso’s beauty and mastery we have not understood it, and thus have not understood the previous books either.

Perhaps Charles Williams put it best:

“The general idea that the Hell is more interesting is true - for those who do not wish to be ‘adult in love.’ Dante did.”

#5: The Divine Comedy is about the logic of the disintegration and reintegration of human love.

What unfolds with inexorable logic? What is it that we see from the perspective of the Goal?

We see that love is the engine moving all things, for good or ill, and that this love can collapse in upon itself in the icy death of desire or find its way into the dance of the “Love that moves the sun and the other stars.”

In either case, there is an narratable itinerary with love as axis.

#6: The Divine Comedy, like most great masterpieces of the tradition, sees love’s drama at work simultaneously in the city and the soul—undergirded by the assumption that one metaphysics unfolds in both.

Here Dante’s principle is that of Plato’s Republic (as well as Augustine’s Confessions). Why is this the case? One illuminates the other because they reflect something more original. They unfold a deeper order, which is simply that of being as such, or Soul in the Neoplatonic sense in which it is not merely the individual but a level of reality’s hierarchy governing the entire world of sense and discursivity.

#7: It is a mistake to read Dante one-sidedly through either Thomas or Averroes. This mistake can be remedied by seeing how both influences are framed by a wider tradition: speculative Aristotelianism and Neoplatonism, which pervade both Christian and Islamic mysticism.

Here one could venture a comparison to the reception of German Idealism. In somewhat cynically reading Dante as an Averroist, if not an atheist, the Straussians are analoguous to the Left Hegelians, who saw Hegel’s legacy as a de-theologized humanism.

But it is also erroneous (and here not only Catholic traditionalists but certain Anglicans can be guilty as well) to see Dante as simply a good Thomist (unless by this is meant the wildest Proclean Aquinas on offer). They correspond to Right Hegelians.

By contrast, if either Averroes or Aquinas is to be read properly, they must be situated within the metaphysical horizon of Neoplatonism, within which Dante also stands. Neither Neoscholasticism nor Straussian readings of Islam do so sufficiently, and so fail both as readings of these figures and readings of Dante. But in addition to Dionysius and Proclus, we must add more Aristotelian forms of speculation, which are separated from the former by the absence of “a One beyond being” and thought in favor of a divine self-thinking inclusive of difference.

One must chart a path between cynicism and shallow literalism. Dante’s exoteric Thomism is certainly subverted, but in the direction of a more speculative, more Neoplatonic metaphysics, not an esoteric political nihilism.

#8: The Comedy is a defense of Christian secularity, of which Dante is the foremost poet. As such it is of particular importance to the modern age’s self-understanding.

Dante is certainly no integralist, as anyone familiar with his views on papacy and empire is aware. But more profoundly, he is a poet of secularism in the broader sense of a unity which proceeds through division. This is not the division of two-tier Thomism’s layer cake, but rather a more holistic self-division which accomplishes the self-return the former makes impossible.

The unity of this division is not the external form, which involves hierarchical subordination. Rather, it is vital in the sense in which soul divides itself to accomplish the activity which is life.

Dante’s vision of erotic and embodied love is both more aware of romance’s distinctive earthiness and more aware of its status as theophany. Similarly, his insistence on the autonomy of secular power is precisely his awareness of its reflection of divine charity.

For him, secularism is precisely the outworking of Christianity, as would later be seen by Hegel or Charles Taylor. In an age in which secular institutions are under attack, Dante can help us see their root in the very logic of Christianity.

#9: The Comedy is also a defense of the possibility of an experience: that of the communication of divine glory to human flesh, which originates in the erotic encounter with Beatrice. Dante’s inGodding, culminating in his vision of Christ, is simultaneously an elucidation and Christological justification of this experience. In multiple ways, this is a true Theology of the Body.

Here I direct the reader to Charles Williams’ Religion and Love in Dante. I only add the suggestion that it is not accidental that Dante’s love of Beatrice is both a) not domesticated by its integration into the order of reproduction and b) more theologically grounded in Christology than are contemporary Roman Catholic reflections on romance.

#10: The metaphysics underpinning all the above appears with increasing intensity in the final books of the Paradiso. It is one of perfect self-division, rooted in the Platonic dilemmas posed by the twin principles of the One and the Dyad, but following Aristotle’s resolution of these through a concrete principle inclusive of division. This Aristotelian metaphysics was further perfected in the development of Christian doctrine. Here Aristotle’s principle is discovered to be the Trinity, and yet more concretely, the Incarnation. We see this in the Comedy’s final Canto.

More on this in future posts, as we journey through the text.