As part of my Theology and Literature class, I am working on a summary of Julian’s Shewings. I thought I would post them here in case someone might find them helpful. Here is the first installment - and the second. I have italicized the sections where the shewings proper are described.

Revelation XIII, continued: Beholding the End of the General Man

In ch. 35, Julian desires to know about a specific person in particular whether they will continue to live well. She is refused a vision of this, and reminded that it is more spiritually beneficial to behold God in all things rather than in one in particular. She reflects on the fact that God does all things which are good, and suffers (or permits) all things which are evil. She defines “rightfulness” as something that cannot be better than it is, and “mercy” as the divine working that lasts as long as sin lasts. God will accomplish rightfulness in us, and once this has been accomplished mercy will cease.

In ch. 36, Julian discusses the deed of salvation which God will accomplish despite the fact that we cannot avoid sinning. (This is different from the mysterious great deed she talked about earlier). This deed begins to be accomplished on earth and is known and rejoiced over in heaven. This deed of salvation has to do primarily with “the general man,” or human nature or the race as a totality, but it does not exclude particular humans in their individuality. God tells her that he doesn’t want Christians to ask for visions of the damned, but to make God their intention and focus. Sufferings, she is reminded, come before great miracles.

In ch. 37, Julian realizes that when God told she would end up sinning, he didn’t just mean her but the “general man” or all her fellow Christians. But God reveals to her that he preserves the totality of those that shall be saved.. She distinguishes between the godly will in the higher part of our soul from the beastly will in the lower part. The higher, godly will never consents to sin and is loved by God as much here below as he will love it in heaven. The lower, beastly will is the cause of all our troubles and does not will the good.

In ch. 38, Julian writes that in the end sin will not be an occasion of sin but “worship.” For every sin which causes us to undergo pain and sorrow in this life will be rewarded with its own particular bliss. She reflects on the various saints and holy people in heaven (including a local St. John of Beverly). Although they were allowed to fall into sin during their lives, this eventually led to greater joy than they would have had if they did not fall.

In ch. 39, Julian reflects on the means by which sin is turned into an occasion of “worship.” When we sin, we undergo purging punishments, which lead to greater maturity. We become aware of and weep over our sin (contrition), which leads us to meekness and humility. And we do penance after confessing them. (She is meditating here on the three wounds she asked for at the beginning: contrition, compassion, and true longing.) God does not cease to love us when we sin and ensures our victory over the devil. Peace and love are always with us, in the highest part of our soul, even when we don’t abide there.

In ch. 40, Julian reflects on God’s sovereign friendship. When we sin, we believe that God is angry, and repent so that he will forgive us. And he does. But what he tells us is that darling, I am glad you have come to be, but I have always been with you and now we are united in love. Julian insists that this does not mean we should seek to sin more to get more of a reward, for the closer we are to God the more we hate sin (rather than just fearing the pain and punishment it involves). Christ is the ground of all true laws, and thus we should always be praying and longing to be kept from sin.

Revelation XIV: The Fortunate Fall of God’s Servant

In ch. 41, Julian reflects on our lack of trust and confidence in prayer, which ends up in a feeling of spiritual emptiness afterwards. The Lord Jesus tells her that “I am ground of your seeking, so how could you not end up getting what you seek?” It is impossible for us to seek mercy and grace and not have it, for we can only seek if God has moved us to seek, and whatever he moves us to seek, he has ordained for us before the foundation of the world. Seeking is a uniting of our will to Christ’s, by the Holy Spirit. It makes us as like him in our current condition as we are by nature. She is told to keep praying, even if she feels nothing. For although we cannot see it, it counts as living prayer and stands before God continually.

In ch. 42, Julian continues to reflect on prayer, and how it springs from the Lord Jesus as ground. The fact that we can only pray if God has first moved us should reassure us that we will get, one way or another, everything we could desire. If we recall everything God has already done before we pray, we would be encouraged. Nevertheless, even though we see that he does all things, it is still our duty to pray.

In ch. 43, Julian again says that prayer unites the soul to God. She reflects on the paradox that God is grateful to us for our good deeds, and yet he is the one who does them! The single purpose of prayer is to be united in the sight and beholding of God. As we await this, we should be flexible and obedient, but we don’t make God obedient to us, because he is always already loving. We, the made, will one day see God, the maker, face to face, delighting in him with all five spiritual senses, as in some sense our true selves hidden in God already do.

In ch. 44, Julian refers back to the soul of Mary she saw in the first revelation, and concludes that human beings, in Trinitarian fashion, see, behold, and delight in God. We have the same properties, in created form, as God, and creature and Creator mutually delight in one another.

In ch. 45, Julian sets out the two judgments, or perspectives, that one can have on the soul. In God’s judgment, which sees our natural substance (the highest part of the soul), we are always blessed and perfect and God does not blame us at all. But in our human judgment, which judges by our changeable sensuality (the lower part of the soul which can incline toward the carnal body), we are sometimes sinners and worthy of blame. Julian struggles to reconcile and hold to both judgments. Although the second judgment is not ultimate from God’s perspective, we cannot simply leave it behind. She points to the Lord and Servant parable as the best answer she has.

In ch. 46, Julian encourages us to long both naturally and by grace to know ourselves, as we are truly in God. We can never fully do so until after this life passes away. She reflects again about the difference between her vision of God having no wrath and the Church’s teaching that we deserve wrath. She writes that God cannot be wrathful for two reasons: it is against the goodness which is proper to him, and because nothing - not only wrath but also forgiveness - comes between the tight union between God and our true selves.

In ch. 47, Julian tells us that she previously thought God’s mercy was him taking away his wrath. But now she sees no wrath in God and chalks up our sin to our blindness and inability to see God. Our failings and mourning over them are dwarfed by the greatness of the soul’s abiding desire for God and the comfort this brings. We can experience this comfort at times even in this life, but it helps our spiritual growth sometimes to experience its absence, including the fall into our (lower) selves.

In ch. 48, Julian reveals that the wrath and contrariness we think is in God is actually in ourselves - a feature of the sense soul when it falls from its natural substance into the world of contradiction and shifting appearance. God’s mercy and grace permit this fall and put it to good use. Mercy desires and accomplishes motherhood and grace royal lordship. God’s mercy consumes our wrath and turns evil to good so that things end up better than they would have without it.

In ch. 49, Julian gives another reason why God cannot have wrath or contradiction. If God had wrath towards us or could be in contradictory states, we would not exist. We only exist because he gives us the peace, simplicity, and stability which keeps us in being while we fall into wrath and contradiction. Our true selves are beclosed and kept safe in his mercy so that we can be restored to ourselves in the end.

In ch. 50, Julian cries to God for an answer to the dilemma she is facing. She sees an apparent conict between a) what her vision has revealed to her of God’s perspective (sin is no deed and the souls that shall be saved were never spiritually dead) and b) the public teaching of Holy Church (we oen sin and fall into spiritual death). What she can’t see in God is how God sees us in our sin, and so she is very perplexed. She works up the courage to ask for knowledge of this, encouraged by the fact that this is not a high secret of God, but something that is relevant to everybody and helpful for salvation.

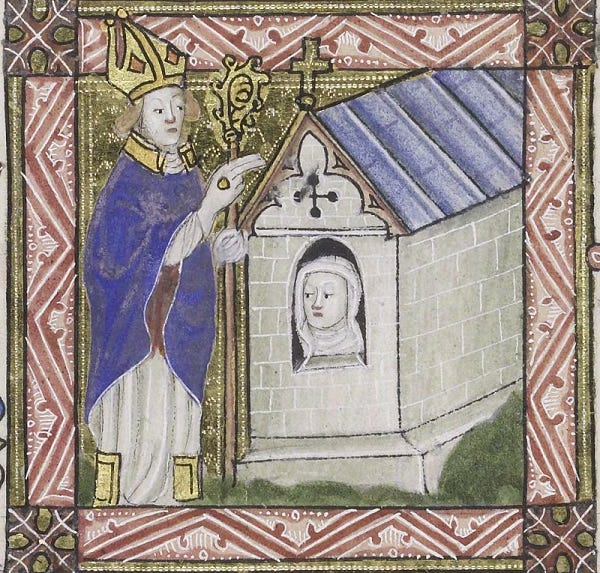

In ch. 51, she sees - in both a bodily and spiritual vision - the example of the Lord and the Servant which is in many ways the heart of this book. In this parable, a Servant is reverently standing read before his Lord, who sits in peace. e Lord sends him o on a task, and the Servant runs uickly to go do it, but he falls into a valley and can’t get up, lying there bruised and alone. One of the eects of this fall is that he is so mentally stunned that he can hardly remember his own love.

Julian is eager to find out whether the Lord will assign his Servant any blame, but he does not. The Servant fell only due to his great desire, and so he is as inwardly good as when he stood ready and waiting on the Lord. The Lord’s disposition or countenance towards the Servant is double: gentle pity outwardly, and inward joy for the rest and nobility the Lord will restore to him.

The Lord resolves to reward the Servant more highly than if he had not fallen. Julian realizes this parable is the answer to her question, but she doesn’t understand it yet. Because although she gets that the Servant is Adam, there are many features which couldn’t apply to Adam as a singular being.

Julian reflected therefore on this parable for many years, and will share the insights which have eased her soul. She reflects on all the details, knowing that many mysteries are hidden in every revelation. The Lord is God, and the Servant is Adam - but at the same time all humanity, for all humanity is one Man in God’s sight. Man is blinded, and can see neither God’s gaze and countenance towards him, nor his natural will and true self in God. She describes the Lord’s regal garments, his face, and his placement in the desert on earth. His pity is for Adam’s sin fall, and his delight is in his Son’s “Fall.”

The Lord’s being in a desert on earth symbolizes that he has made the human soul his city or dwelling place. The servant is outwardly clothed in a dirty and plain robe, which doesn’t seem fitting for the Lord’s presence, and seems to indicate he has been working for a long time. But inwardly he is fresh, ready to work for the first time. The job he was sent out on was to garden the earth and prepare food and drink for the Lord.

God’s Son, the Second Person of the Trinity in his divinity, is included within and symbolized by the Servant, as well as Adam, or all humanity. Adam (humanity) and the Lord’s Son (divinity) constitute one Man. They are so united that when Adam fell, God’s Son fell. The weakness we have is from Adam, the inward goodness from Jesus Christ.

The Servant standing ready to do the Lord’s will is also the Son, standing in Adam’s clothing, ready to do the Father’s will and “fall” into the womb of the Virgin Mary. The humanity of Christ is all humanity that shall be saved, the members of the body whose Head he is.

The broken and rent clothing of the Servant thus also represents Christ’s scourgings and the crown of thorns which ripped up his esh. But God’s Servant, having descended unto hell and liberated the saved there, is transferred from the laborious left to the restful right, bringing us with him as God’s crown and “worship,” his beloved spouse.