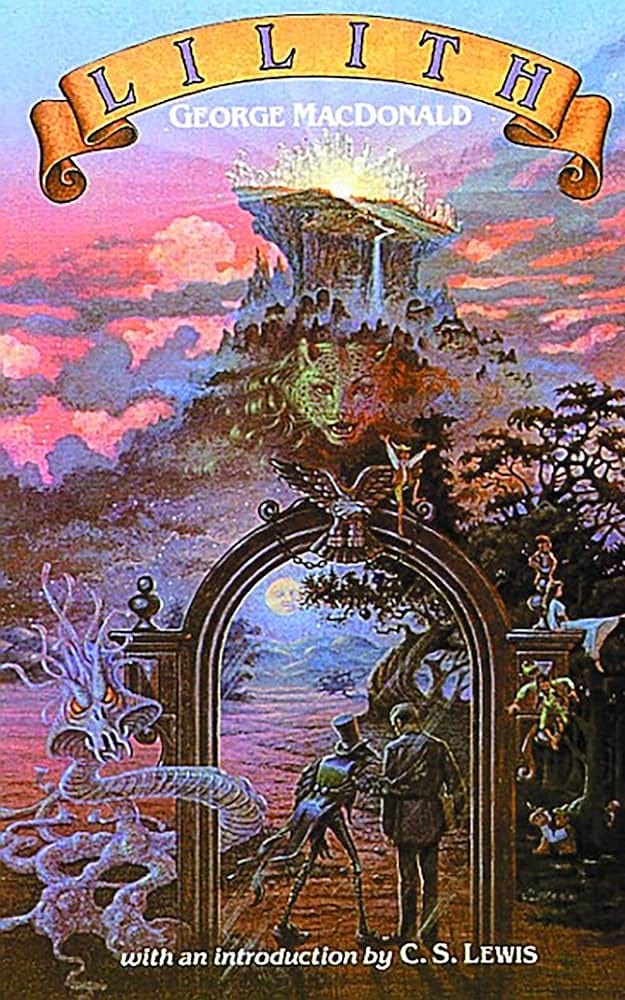

I’m teaching George MacDonald’s fantasy novel Lilith in my Theology and Literature class right now, and I think MacDonald really helps us get to the core of the debate between universalism and theological voluntarism.

Here’s a summary I made for my students:

Theological Voluntarism in Five Theses

God’s authority to punish comes solely from his having created us, and so he can do with his creatures what he wills (his voluntas)

God is good, but his goodness is beyond goodness as we perceive it and so he can’t be held to the standards of earthly goodness (he is a good Father, but the analogy to human fatherhood doesn’t work). It has to be accepted on authority and blind faith.

Punishment can be “punitive” or “retributive”; that is, can be deserved even if it doesn’t make the person better or restore them

Since we have come from nothing and have free will, we can become radically evil all the way down (choosing hell for ourselves) and God’s not on the hook for that.

Therefore, an eternal hell can be consistent with justice and divine “goodness”

MacDonald’s Universalist Response

Having created from nothing (without the will of creatures) gives God an even greater obligation than human parents have to ensure good outcomes for his creatures

God’s goodness is more good than ours, but this means he needs to be *at least* as benevolent as we expect human fathers to be. It is recognizable to and can be held to the standards of earthly goodness, even if it exceeds it

Punishment only ever makes sense as restorative, aimed at the healing and return of the one punished. It is liberating them from the unfreedom they have chosen

Since being made from nothing actually means coming from God’s glory and having an eternal true self, we can never will to become wholly evil. We can live in the “library” of our soul, where we create a false self, without suspecting that in the “attic” of our soul we continue to will the good. Additionally, God is responsible for putting us in the arena of freedom without our will and so is still on the hook.

Therefore, an eternal hell is unthinkable. God’s creation is only justified if every creature comes to freely will for itself its originally unfree origin.

It seems that "goodness" and "pleasure" are somehow inextricably linked (scripturally and intuitively). "For this is good and PLEASES God our Savior - who would have all people to be saved"...

(and - "God takes no PLEASURE in the death of the wicked")

Any thoughts?

Thanks for this illuminating contrast!

I started reading Lillith last night and fortuitously found this blog post!

I like how this makes clear that starting from God as voluntas, will, being such as to aim for the good, is not already good, so God is instead understood as unlimited power. What is missing here is the other horn of the dilemma: God as good. As *good* a structure of obligation is built into God's acts: they are not divine because all-powerful but because fully what they *ought* to be.

The obligation e.g. the one we recognize to our children does not enter from outside in the latter conception but is added as an afterthought in the first; such afterthoughts disqualify themselves, since what they are added to is supposed to explain *them*.

No obligation is built into libertarianism, or the libertarian. This accounts for its propensity to moral indifference.