"Sin is No Deed": On Evil's Unreality

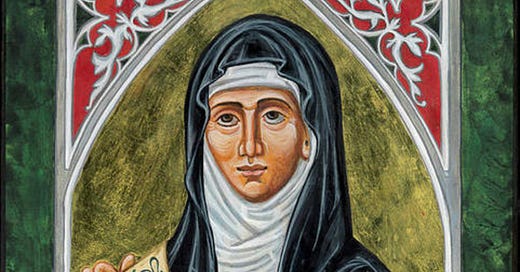

Reading Julian of Norwich Through George MacDonald's Lilith

In my Theology and Literature class, my students have just finished reading George MacDonald’s Lilith, and we are now turning to Julian of Norwich’s Revelations of Divine Love. The two texts are a natural pairing; their metaphysics of the true/false self and the parasitic (and thus transitory) nature of evil are virtually identical. The target in the crosshairs in both cases, too, is the same: theological voluntarism.

The following is an attempt to interpret Julian’s enigmatic statements in chapter 11 with the help of illustrations from MacDonald’s Lilith.

The Problem

Julian writes that:

“Sin is no deed”

“How should any thing be amiss.”

“God doeth all thing.”

These statements initially seem ridiculous, for several reasons.

The first and second claims fly in the face of the evil we experience everywhere; things very much seem to be amiss. How can one assert evil’s unreality to the one who has experienced abuse and victimization, to say nothing of non-moral evils like the sudden onset of cancer?

Even if we set the evidence of experience aside for the moment, the third claim would seem to make God the agent of, and thus is the one ultimately responsible for, actions what we would regard as unequivocally evil.

Of course, this is why Julian combines the third claim with the first; God can only be recognized of doing all things if certain actions are denied to be “deeds” or “actions” at all. But this qualification only increases our confusion.

How can evil fail to be a “deed”? How can it prove fundamentally unreal?

I think Lilith offers a few key clues.

Worlds of Appearance and Reality

On of MacDonald’s key claims in Lilith is that we are stuck in the world of appearance and do not see things as they are in the world of reality. The fantasy world into which the protagonist Mr. Vane enters has the benefit of making this obvious, but the novel suggests that this was equally true of him while he was in “our” world. Mr. Vane’s spiritual journey is supposed to help him escape from the realm where mere appearance/opinion holds sway. He must glimpse the world of reality which shines in the world of appearance like the reflection of the moon which guides his travels, but which itself exists above the possibility of doubt and the deception of bare seeming.

I want to suggest that for Julian, in the world of appearance, there “is” sin and things are amiss. But in the world of reality, which is where are all real “deeds” are, there is no sin and things are not amiss. Dwelling in the wrong realm (which corresponds to a superficial level of our soul), we lack proper perspective on evil.

Julian writes in chapter 11 that if things seem not to correspond to God’s purpose, “our blindness and unforesight is the cause.”

Our being on the level of the world of appearance is the cause of sin in a double sense.

We sin because we are captured by the appearances of things rather than reality. The sin appears good and attractive to us when it is not.

We think that sin a “deed” and “exists” in the philosophical sense because we live on the level of appearances and not the world of reality, the realm which defines what is actually a deed and what actually exists.

If we were on the level of reality, where God is, we would see that sin is not a deed and is not real and does not really exist in the deepest sense. (This does not mean it is not “real” in a qualified sense for those of us who live in the world of appearance and have lent it the reality of our lives). The monsters of the MacDonald’s Bad Burrow may be a “vain show” but that does not mean they cannot harm us!

Evil as Parasite

MacDonald, following the Augustinian tradition, does not view evil as a thing or substance, but rather a “twist,” “absence,” or “lack” of goodness. It is a parasite, like Lilith, who survives in vampiric fashion on the blood of children, or like the Shadow who has no “thick to him.”

Julian, I argue, has translated this insight from the register of substance to action. Sin is not a deed, just as it is not a substance. It is a parasite on the true “deeds” of the world of reality.

At the core of every evil being, for MacDonald, is a true self which is good. Julian is saying the same thing about evil deeds. The innermost core of every deed, like the innermost core of every person, is good, and in fact, is God acting in us. This is no different from the fact that our true self is the divine version of us, endlessly born from the heart of God himself. Julian thus holds that there is a part of every action which lives in the world of reality, and that good part alone is the real deed or action.

The Perspective of Eternity

Over and over again, in the labyrinth-like plot of Lilith, MacDonald shows that the wrong move turns out to be the right move. Seen from the perspective of the end, Mr. Vane’s errors and deviations from the path constituted the path. Mr. Vane’s miseducation of the Little Ones unleashed the troubles which made them mature; the tears which flow from not having sought the water flowing beneath the earth are themselves the flow of that water.

Seen from the perspective of the end, Mr. Vane and Lilith were on their way “home” the whole time, including in their most resolute attempts to flee from it.

Julian’s statement that “sin is no deed” and that nothing is “amiss” participates in the same perspective.

From our perspective in time, when evil “acts” have not been redeemed and their true inner core remains hidden, it seems that sin exists and that things are amiss. But God does not live only in time and God sees things from the perspective of the end, which is the same as the perspective of the world of reality.

As Eve puts it in Lilith: “To our eyes, you were coming home the whole time.”

From the perspective of Adam, Eve, and Mara, Mr. Vane’s sins were no “deed” and nothing was amiss, because they saw his actions in their true innermost core, as they would be once he had undone the bad part of them. His detours were the crooked paths the Lord makes straight.

Redemption gives a retroactive meaning to the past, placing at its heart the innermost core that alone makes it a deed.

Lilith’s clenched hand and her stubborn repentance to repent are no more. Now her severed hand, planted in the desert, has only the meaning which was truly its core along: it is the source of the waters which restore creation.

Her sin is now “no deed,” and the only real and good part of her act of closing her hand is its opening to provide the moisture which drenches the land and drowns its monsters. There is “nothing amiss”; and from the perspective of those who have journeyed with her, nothing ever was.

Julian’s view is much the same. When God’s purpose is realized, the innermost core of every deed will be revealed, and every other aspect of it will be destroyed and maybe even forgotten. Sin will only be behovely.

There is kind of a backward logic here - in the end, sin “will have been” no deed. Once our sins receive their new meaning and the evil parasitic upon them is undone, all that remains is God’s good action in them - which is now also fully ours.

Reality is constituted by appearance’s undoing of itself as mere appearance. It is the felix culpa, the recoil which seems to be a second moment but establishes itself as the first.