The Hyperphatic: Paradox or Dialectic?

McGinn, Milbank, and Zizek on the coincidence of opposites

In an interview with Commonweal Magazine from 2022, Bernard McGinn schematizes the principles of theological speech which govern mystical theology from its origin in Dionysius. The elder statesman of the guild begins with the familiar dyad of kataphasis (“yes-saying”) and apophasis (“no-saying”): a distinction which is the first principle of theological speech.

Within this dyad, it seems that the apophatic must be privileged. “The apophatic is always higher because God ultimately is not like anything that we know”; this asymmetrical priority is the second principle.

But crucially, McGinn notes that the thought of the Areopagite in some way moves beyond this opposition, leading a third principle, the hyperphatic beyond.

He writes:

But there’s a third principle, what I call the hyperphatic—the ‘beyond-saying.’ God is beyond both affirmation and negation, insofar as we know these, because we do so from a limited, finite perspective. So according to Pseudo-Dionysius and many other mystics, you eventually reach the level of what I call the hyperphatic: God is beyond both affirmation and negation in a realm that we really cannot talk about. We talk around it, and silence is where we finally wind up, in adoring silence of the mystery.

There seem to be at least two closely related reasons for the introduction of this third principle of the hyperphatic.

Why Hyperphasis?

The first is that negation, or apophasis, can easily be misunderstood as, or morph into, a subtle mode of kataphatic capture. In listing what God is not, we may deceive ourselves into believing we have thereby gotten ourselves closer to understanding God’s essence. Our negations become secret affirmations, like the sculptor who chisels fragments off stone off a marble black in order to reveal (or constitute) a determinate form by subtraction. Alternatively, we could think that God is, positively, Nothing or the Void: reify negation itself into a kind of positivity. The hyperphatic is meant to keep either form of this misunderstanding or inversion at bay, to make sure that negation stays negation.

The second is that even a priority of the apophatic over the kataphatic preserves an opposition between the two, and this opposition must be overcome. God, and thus the approach to God, cannot be the higher in a two-term opposition. God, surely, is beyond all contradiction. After all, again and again in the mystical tradition God is revealed to be the coincidence of opposites. Or again, to put the same thing differently, there is some vague awareness that kataphasis cannot be left behind. Thus the priority of apophasis cannot be the last word.

Contemporary Paradigms of the Hyperphatic

This move to the hyperphatic is thus quite understandable, and even inevitable. However, everything hinges on understanding this third principle rightly. In what way do we pass beyond the opposition of the apophatic and kataphatic? What shape is given to the coincidence of opposites? Not all hyperphatic resolutions are the same.

There are two main forms in which the hyperphatic beyond is figured in contemporary discourse. The first is as silence, and the second is as doxological praise.

We see something of the first in McGinn’s comments above (although there is a hint of the second as well).

McGinn writes that “God is beyond both affirmation and negation in a realm that we really cannot talk about. We talk around it, and silence is where we finally wind up, in adoring silence of the mystery.”

What is the hyperphatic, then: the silence into which we fall in the failure of both affirmation and negation.

It does not require a master of suspicion to see the problem here. While silence is, to be sure, not exactly the same as negation in speech, it seems quite clear that hyperphatic silence leans more towards apophasis than kataphasis.

This hyperphatic “resolution” is therefore one-sided and still operates under the concealed priority of the apophatic and negative. Only now it is linguistic mediation as a whole which is negated rather than a determinate proposition, attribute, or name.

Some postmodern thinkers like Jean-Luc Marion (and others too numerous to list) therefore prefer to speak of doxology (praise) as the hyperphatic’s native tongue.

The hyperphatic register is associated with the shift from the predicative order of speech (whether positive or negative) to the order of worship and adoration (note McGinn’s reference to an “adoring” silence; these figures attempt to imagine this adoration as verbal). John Manoussakis writes that “the only logos properly addressed to God is doxology”; this is Marion’s “discourse of praise.”1

Here there is an address and encounter beyond signification, beyond reference, beyond objectification. This hyperphatic seems a truer resolution for it can do more justice to the hyperphatic: the rich language or prayer and liturgy has a place in it.

Yet when one reads Marion carefully, it becomes clear that the kataphatic has been “preserved” at the cost of the determinate content we originally thought was proper to it. You can sing a hymn which names God as Love or even as a Mighty Wind, but according to Marion this is no longer understood to be affirming anything at all, let alone something definite. The “facts of the language of praise require that one no longer see in it a predication.”2

This is ultimately a speech which is, from the standpoint of meaning, convertible with silence. Perhaps more precisely, in his early work, John Panteleimon Manoussakis says it is not speech but music: “it would be a mistake to regard hymn as it were another form of speech (‘sung speech’); hymnody properly belongs to music (music with words, i.e., song).”3

This is hardly theologically or philosophically satisfactory (in his defense, Manoussakis has since changed his mind). Again, this is not the apophatic proper, but the alleged synthesis clearly leans to one side; determinate content is definitely left outside this alleged coincidence of opposites (if this term applies at all).

Indeed, one is hard-pressed to find an account of the hyperphatic which is not marked by this imbalance.

The Way of “Paradox”

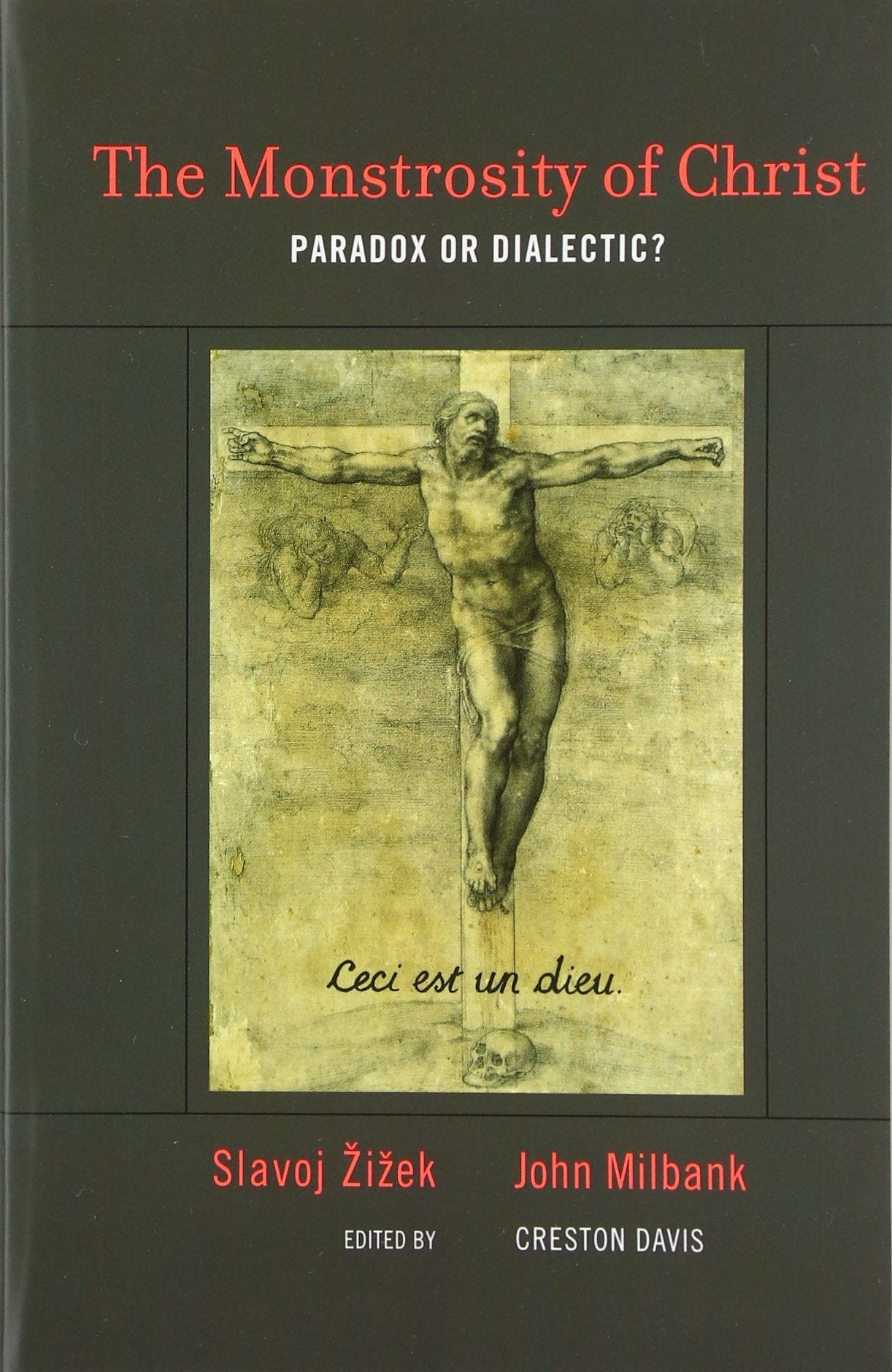

I’m tempted to suggest that this is due to an underlying commitment to understanding the coincidence of opposites as “paradox” rather than “dialectic” (to borrow terms from the scintillating debate between John Milbank and Slavoj Zizek).

The hyperphatic, formally speaking, takes as its starting point a tension or opposition between two terms and seeks resolution in a third.

One way of understanding this resolution is elucidated by Milbank as “paradox”:

If to be hidden is to be shown (against the background of ‘mist,’ as including a misty density proper to the thing itself ), and therefore to be shown is to be hidden, then this implies not an impossible contradiction that must be overcome (dialectics) but rather an outright impossible coincidence of opposites that can (somehow, but we know not how) be persisted with. This is the Catholic logic of paradox—of an ‘overwhelming glory’ (para-doxa) which nonetheless saturates our everyday reality.4

That is, in paradox, two terms are thought of as one in a third which is beyond their (apparent) opposition. In this third, they are revealed (by stipulation) to have been always at peace in their difference. There is no resolution of a contradiction because, viewed properly (from the standpoint proleptically occupied by paradox), there never was any contradiction. Violence is not overcome but denied. There is no tragedy.

The problem, of course, is that paradox proclaims all this by stipulation. The world we actually inhabit, and which constitutes the basis of the only clarity and intelligibility available to us, there is violence and contradiction. There is tragedy—at least phenomenally (“for us”).

This recognition is internal to paradox. It openly admits that it cannot demonstrate this harmony, or even its possibility; it does not claim to have itself overcome the apparent tension, it claims it to have been overcome (or better never arisen) in the thing itself. From the epistemic standpoint we in fact inhabit, what paradox proclaims is, and remains, “impossible.” We merely assert that there is no contradiction; “we know not how.”

One makes the (Kierkegaardian? fideistic?) choice to believe that things are not what they appear to be. This is belief in a higher resolution which is free of all negativity. Original difference without contradiction: the coincidence of opposites. Never dialectic.

The object (reality/God) is free of the contradiction that is manifestly present in the subject who clings to paradox (between the assertion of coincidence and the “not knowing how”). Paradox posits the purity of the in-itself, from within the bifurcation of the for-us. We project ourselves into the standpoint which we in that very moment deny we occupy. In the denial of contradiction in the object, another contradiction arises: between the in-itself and the for-us, subject and object. It is obviously senseless to retort that in-itself the contradiction between the in-itself and the for-us is overcome!

There is a kind of meta-apophatics here: the point of coincidence of hiddenness and manifestation is itself hidden. And hence if we wish to say that the relationship between apophasis and kataphasis is paradoxical, then our explanation of their coincidence will itself be, in second order fashion, apophatic. Hence it is necessary that all resolutions of the tension between apophasis and kataphasis which have paradox as their form will one-sidedly lean toward the apophatic.

But is there any alternative?

The Way of Dialectic

Zizek’s response to the quotation from Milbank above is telling, for it brings out both 1) the constitutive role apophasis plays in his paradoxical vision and 2) the exclusion of negativity.

Note here also the precise reference to beauty, which has to be given its full weight: a totally transparent rational structure is never beautiful; a harmonious hierarchical edifice which remains partially invisible, grounded in an opaque foundation, is beautiful. Beauty is the beauty of an order mysteriously emanating from its unknowable center. . . . Again, while I fully recognize the spiritual authenticity of this vision, I see no place in it for the central Christian experience, that of the Way of the Cross: at the moment of Christ’s death, the earth shook, there was a thunderstorm, signaling that the world was falling apart, that something terrifyingly wrong was taking place which threw the very ontological edifice of reality off the rails. In Hegelese, Milbank’s vision remains that of a substantial immediate harmony of Being; there is no place in it for the outburst of radical negativity, for the full impact of the shattering news that ‘God is dead.’5

Zizek argues that Milbank’s vision—of ultimate harmony in the immediacy of Being, projected into an unknowable beyond—is not Christian but pagan. In doing so he clearly points to the governing meta-apophatics and the aversion to negativity. Is not Christianity, he replies following Hegel, distinguished by its claim that God is revealed, and that God submits in Christ to the ultimate negativity of anguished subjectivity?

The encounter of opposites in Christianity, that is, does not occur in the harmony of an inner-Trinitarian “beyond” of peaceful difference but in Christ’s person suffering the agony of the cross. Or with a little more nuance than one finds in Zizek: the two are one and the same, since the immanent Trinity just is the economic Trinity. the Lamb has been slain from the foundation of the world (Rev. 13:8).

What dialectics suggests is never, as Milbank wrongly suggests, a simple “overcoming” of contradiction. It does not aim at the harmony of Being, a resolution which fruitlessly attempts to expunge from itself the tragedy and contradiction through which it was forged (the so-called Hegelian “slaughter-bench” of history). This is closer to a description of Milbank’s view, as Zizek shows.

Rather, dialectics seeks to show how the contradiction is in the object itself. The resolution is the “parallax shift” in which the problem, viewed from another angle, is already the solution. As always in the Hegelian rejoinder to Kant, the gap which seems to separate us from reality is shifted into the object’s interior.

Negativity and finitude do not separate us from God, for in the Incarnation God has eternally made them the beating heart of his divine life. The phenomenality, or subjective standpoint, from which this world “appears” as tragedy and opposites “appear” as contradiction is not a feature of some primordial illusion (as in the metaphysics of antiquity, a Fall from the One, both of which must be “presupposed”) but something experienced on the cross by God himself. The cut of subjectivity is inscribed in the Real.

A Dialectic Hyperphatics

So what does this mean for our original question: how to understand the term “hyperphatic,” and with it the overcoming of the division between apophasis and kataphasis?

We’ve seen the problems associated with associating the hyperphatic with silence and with doxology, and more generally the difficulties which are entailed by the paradigm of “paradox.”

What would it mean to understand the hyperphatic in dialectical fashion?

Let us take a step back to consider the form transitions take generally in Hegel’s Science of Logic. As one attempts to think a particular thought-determination (for instance, “being” in the famous opening of the Logic), one discovers that precisely in trying to think this thought as totality, and nothing else, one is driven to think its opposite (“nothing”). In trying to think “being” as thought’s object, I end up thinking “nothing.” Being turns into its opposite, and we are left with a contradiction, a contradiction which is not contained in the object I initially set up as exhausting thought.

The key to understanding Hegelian dialectic is what happens next. I do not attempt to “get rid of” this contradiction, seeking some third term which is free of it. Rather, I seek to think this contradiction as real, rather than falling outside reality into my subjective reflection. I seek to rethink this contradiction not as a problem, but as a formula for a more adequate description of thought’s object. The contradiction in which out thought seemed to fall apart—for instance, the vanishing of “being” into “nothing”—is viewed from another angle, not a failure but a further objective determination of thought’s object: in this case, “becoming.” This is the logic of “determinate negation.”

As Sebastian Rödl puts it, we must reconceive the contradiction no longer as regress but as self-return. The problem, properly redescribed, is the solution.

(For instance, near the end of the Logic, we are confronted with a double regress when thinking external teleology. Spelling out the thought of an “aim” to be realized in some material, we end up with a series in which every member is at once means and end. We never encounter pure means or pure end, and thus our thought seems to fall apart. But the key shift is not to move beyond this contradiction, but see it as objective. A series in which ever member is means and end is precisely the definition of the next thought-determination: organism!)

What does this mean for apophasis and kataphasis (another name for the problem of transcendence more broadly)?

The oscillation between apophasis and kataphasis must not be resolved in a higher third (which always turns out to be the apophatic in disguise). The oscillation itself, redescribed, is the truth of the extremes.

God is not above apophasis and kataphasis, but their objective dialectic. God is this existing contradiction as the process of Incarnation, in which God simultaneously generates revealed and knowable content (the Incarnate Christ) and the unknowable horizon generated by this revelation as its ground and backdrop.

The Ineffable is a product of speech; divine transcendence depends on the utterance of a Word.

As Slavoj Zizek puts it,

It is not that we need words to designate objects, to symbolize reality, and that then, in surplus, there is some excess of reality, a traumatic core that resists symbolization—this obscurantist theme of the unnameable Core of Higher Reality that eludes the grasp of language is to be thoroughly rejected; not because of a naïve belief that everything can be nominated, grasped by our reason, but because of the fact that the Unnameable is an effect of language.6

Without this dialectical solution, we are faced with the problem of divine transcendence so ably brought out by Damascius. As Jean-Louis Chrétien put it: Greek apophatic thought was in danger in culminating in “a silent and unknowing adoration of what is so far away that it cannot even be adored, for this would mean positing a relation with it and thus make it lose its dignity.”7

One can only articulate, without performative contradiction, divine transcendence and ineffability as a (sublated) moment within the movement of Incarnation. Even negative theology, if it is not to undo itself, presupposes Incarnation and deification.

It is necessary that this speech [of adoration], if it must be and be true, be itself divine and infinite, while allowing the finite being to hand over to it its own [finite speech] and to participate in [divine and infinite speech]. If the cult of God is impossible because it is always profane, it is necessary, if it must be and be true, that it be itself a divine cult, while including the finite being and sanctifying it. If the adoration of the creator by the creature is impossible, it is necessary that adoration, if it must be and be true, go from the creator to the creator, from God to God, be an infinite adoration of the infinite by the infinite, while catching the finite in its circle.8

God only exists as this circle, this real contradiction. Only in this movement of self-mediation—Jesus Christ who makes the unknown Father known—does God return to himself, but as this is an eternal happening this return has always already occurred.

The Incarnation of the Word, more than the speech and silence it generates, is as act the true hyperphasis, not as paradox but dialectic. Apophasis and kataphasis are not originally acts that “we” perform, but moments in God’s hyperphatic self-utterance into which we are incorporated. They fall within the interior act which is God’s self-externalization.

Manoussakis, God After Metaphysics, 74; Marion, The Idol and Distance.

Marion, The Idol and Distance, 187, 191.

Manoussakis, God After Metaphysics, 107.

John Milbank and Slavoj Zizek, The Monstrosity of Christ: Paradox or Dialectic?, 163.

Ibid., 249.

Slavoj Zizek, The Puppet and the Dwarf: The Perverse Core of Christianity, 70.

Chrétien, The Ark of Speech, 68.

Chrétien, “La limite de la metaphysique selon Malebranche,” La voix nue, 296.

“What would it mean to understand the hyperphatic in dialectical fashion?” Yes, yes—that’s the question. So much of contemporary “apophatics” is a form of kataphasis in despair—a pious skepticism. What you’re articulating here also hints toward why Hegel’s unapologetic quest for the unity of thinking and being is *not* some totalizing endeavor but a desire for theosis. Thanks for this continued generative work.

Good stuff! If you favor more Zizek’s description of dialectic over Milbank’s paradox, are there also areas in which you feel Zizek falls short? Isn’t Milbank’s peaceful difference an attempt to ground finitude and diversity while preserving at least SOME sense of divine aseity? Would you say Zizek has accomplished an appropriate theology of the peace of the divine nature?